Cast: Gregory Peck, Dorothy Mcguire, John Garfield, Anne Revere, Celeste Holm

Genre: Drama, Romance

Other Nominees: The Bishop’s Wife, Crossfire, Great Expectations, Miracle on 34th Street

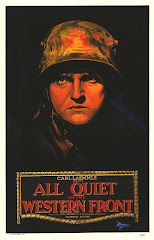

It is not surprising to learn that the three Best Picture Oscar winning films post WWII all dealt with socially conscious themes. We had already seen alcoholism dealt with in The Lost Weekend in 1945 and veteran rehabilitation the subject in The Best Years of Our Lives in 1946. Completing this “trilogy” the 1947 winner turned its attention to racial bigotry and anti-Semitism in Gentleman’s Agreement. With the details of the Holocaust and all its atrocities emerging, I imagine it was hard not to find the subject of bigotry prevalent everywhere in life. In fact Gentleman’s Agreement shared the theme of tackling anti-Semitism with another nominee for Best Picture in 1947, Crossfire. With the evil of Nazism gone from the world perhaps it was only right to look around and attempt to purge any similarities to the regime at home and it appears that anti-Semitism was very much present in American culture. While it goes without saying that it never reached the lunatic levels of Nazism the same seeds of hatred existed and I understand that they demanded exposure.

In Gentleman’s Agreement Gregory Peck plays Phillip Green who had recently moved his family, his son and his mother, to New York City. Upon meeting with the editor of the liberal magazine he writes for Phillip is tasked with exposing anti-Semitism in the city. Initially he struggles to come up with the “right angle” and feels that the facts and figures lack any real insight into how it must feel to be at the receiving end of any injustice he perceives. Then in a moment of clarity, Phillip decides to take on a Jewish persona to personally discover the actual attitudes of people in a town where very few people know him. From there the film proceeds to display example after example of an underlying bigotry and hatred that seems to be everywhere.

The examples come thick and fast. While experimenting with his new identity, Phillip finds that applications sent regarding open job positions are rejected when the name implies the person is Jewish, while the same application with a non-Jewish sounding name is accepted for an interview. He discovers that landlords similarly reject rental applications and strive to keep their buildings free of Jewish people. In one scene a doctor discourages seeing a Jewish specialist on the grounds that the patient will be cheated. He quickly makes excuses and leaves when Phillip discloses his “religion”. When Phillip attempts to make reservations at a swanky hotel his request is rejected as management strive to restrict customers to non-Jewish guests.

While these examples very successfully demonstrate the anti-Semitism in society, the more impactful demonstrations seen in the film are also the more subtle. There is enormous strain put on the blossoming relationship that Phil has with his editor’s daughter Kathy. While their relationship has few problems and they seem a perfect match for each other we see in Kathy an acceptance of the bigotry as being a part of life. When she first learns of the scheme she reacts poorly before attempting to save face:

Phil Green: I'm going to let everybody know I'm Jewish.As the film progresses it becomes clearer to Phil that he had not simply caught Kathy off guard and that even bigger than the problem of outright discrimination was the subtle acceptance that “nice people” had for anti-Semitism. It is a lesson that Kathy learns before the films end but it also becomes the key theme of the film. Just as Phillip could not get his point of view across with pure facts and needed an emotional angle to tell the story the film too cannot get the problems of anti-Semitism across by simply giving examples and needed to explore the emotional impact the divide had on relationships. This demonstration of bigotry being accepted and of the impact it has on Phillip’s relationship with Kathy is where the true power of the film lies.

Kathy Lacey: Jewish? But you're not! Are you? Not that it would make any difference to me. But you said, "Let everybody know," as if you hadn't before and would now. So I just wondered. Not that it would make any difference to me… … Phil, you're annoyed.

Phil Green: No, I'm just thinking.

Kathy Lacey: Well, don't look serious about it. Surely you must know where I stand.

Phil Green: Oh, I do.

Kathy Lacey: You just caught me off-guard.

Phil Green: I've come to see lots of nice people who hate it and deplore it and protest their own innocence, then help it along and wonder why it grows. People who would never beat up a Jew! People who think anti-Semitism is far away in some dark place with low-class morons. That's the biggest discovery I've made. The good people! The nice people!A second relationship impact is shown between Phil and his young son Tommy. When Tommy learns that they are playing a game of pretending to be Jewish he begins to ask questions of breakfast one morning. I really enjoyed this simple scene where Phil struggles to explain bigotry and why it exists to an innocent child. It reminded me of the sad fact that one day I will have to explain similar things to my own child.

Tommy Green: What's anti-Semitism?Tommy plays along with the game of pretending but the pain that Phil feels when his child begins to be bullied is more powerful than any of the examples mentioned earlier. What at first is just a game to Tommy becomes much worse when the local kids begin to ostracize him. After being bullied one afternoon Tommy arrives home with tears in his eyes. A Jewish friend of Phillips tells him that now that his children have felt the sting of bigotry, he has a complete understanding of what it feels like to be Jewish. This friend goes on to describe comforting his own child who does not understand why he cannot play with other kids or why they are rejected from attending camp.

Phil Green: Well, uh, that's when some people don't like other people just because they're Jews.

Tommy Green: Why not? Are Jews bad?

Phil Green: Well, some are and some aren't, just like with everyone else.

Tommy Green: What are Jews, anyway?

Phil Green: Well, uh, it's like this. Remember last week when you asked me about that big church, and I told you there are all different kinds of churches? Well, the people who go to that particular church are called Catholics, and there are people who go to different churches and they're called Protestants, and there are people who go to different churches and they're called Jews, only they call their churches temples or synagogues.

Tommy Green: Why don't some people like them?

Phil Green: Well, I can't really explain it, Tommy.

That moment where Tommy arrives home also becomes the pivotal moment between Phillip and Kathy. Upon seeing him upset Kathy embraces the crying Tommy and soothingly tells him that “it’s not true. You're no more Jewish than I am. It's just some horrible mistake.” This proves to be the final straw for Phillip who is enraged that rather than explaining to his son that the bullying of Jews is unjust and cruel, she chose to comfort him with the knowledge that he was above being Jewish. Not only does Phillip realize the jeopardy that he has placed his son in, and the injustice of that jeopardy, but this moment also solidifies that idea that good people are propagating anti-Semitism as much as any bully or bigot is. This indifference to injustice becomes the films key message.

As I watched Gentleman’s Agreement I could not help but think about Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird, a character who shares a lot in common with Phillip Green. Both are fathers attempting to raise children who see beyond the labels placed on people by the color of their skin or by their religion. Both fathers are forced to explain bigotry to children whose innocence cannot comprehend the complicated reasons of why such hatred manifests itself between different people. Both fathers attempt to stand up against society and show their children that they can behave differently than those around them. In particular I thought about To Kill a Mockingbird and the continued struggle to treat all people equally when I listened to the words of Phillips mother as she looked to the future:

I suddenly want to live to be very old… Very. I want to be around to see what happens. The world is stirring in very strange ways. Maybe this is the century for it. Maybe that's why it's so troubled. Other centuries had their driving forces. What will ours have been when men look back? Maybe it won't be the American century after all... or the Russian century or the atomic century. Wouldn't it be wonderful... if it turned out to be everybody's century... when people all over the world - free people - found a way to live together? I'd like to be around to see some of that... even the beginning. I may stick around for quite a while.It has been over 50 years since Mrs. Green first said those words to her son and although we have not reached the utopian vision she had of all people finding a way to live together I’d like to think that we are still moving in the right direction. That however is a debate for another day.

Up Next: Hamlet

No comments:

Post a Comment